Faculty Spotlight: Cheryl Crowley Hacks Haiku

Cheryl Crowley is an Associate Professor in the Department of Russian & East Asian Languages & Cultures. She teaches courses on Japanese and East Asian literature and culture. Her main research interests are the literature and art of the early modern period in Japan (1603-1868), and most of her publications focus on haikai, the ancestor of modern haiku. She is the interim director of the Emory East Asian Studies Program, former president of the Southeast Conference of the Association for Asian Studies, and associated faculty of the Emory Department of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies. Crowley joined Emory’s faculty after earning her Ph.D. in Japanese literature from Columbia University in 2000.

You recently won the CFDE’s Scholarly Writing and Publishing Digital Track Award. Can you describe the project that got you there?

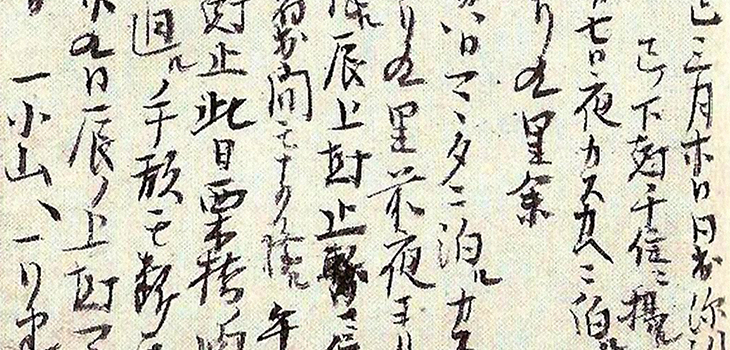

Cheryl Crowley: The project itself is called Hacking Haiku. I’ve been partnering with the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship, working Sara Palmer, Brian Page, Meghan Slemons, Lawrence Hamblin, and former Digital Humanities Strategist Brian Croxall. We’re working to digitize Taorigiku, or Hand-picked Chrysanthemums, a travel journal written by the Japanese poet Tagami Kikusha in the nineteenth century. Kikusha wrote haikai, the genre now called haiku. Travel has long been an important activity of haiku poets; historically they would travel to famous places and beautiful sites and write poems about each, like we might take pictures today. Kikusha’s journeys were a combination of religious and literary pilgrimage. At the places she visited, she met with other poets or other people like clerics, artists, and musicians who were inspirations to her. Later in life she put together a memoir, using the poems she’d written on her journeys, drawn together with prose narrative passages and some of her paintings, basically retracing her journey. The result is similar in some respects to a photo album, with imagery partly in words and partly in pictures. This is a journey through space and time, through literature, history and landscape, and we can bring these multiple aspects of the work together in one place in a digital environment. So far, we’ve been creating a database of the hundreds of poems in Hand-picked Chrysanthemums, linking them to the GPS coordinates of the sites she visited, to the names of the people with whom she interacted, and to literary devices, like the kigo — seasonal words — used in the poems. We’ll be able to take that information and link it with various visual elements, like maps of her route and photographs of the places and things she writes about.

How do you incorporate that work into your teaching?

CC: The digital format offers a great way to present this complex work in a highly accessible manner. For students, Hand-picked Chrysanthemums might seem quite difficult in the sense that it’s from a long time ago and far away; even though Kikusha’s writing focuses on experiences most of us can relate to pretty well, she’s speaking from a context that would be unfamiliar to most students: she references geographical sites that students probably do not know about and mentions many objects, animals, and plants that they wouldn’t recognize either. The digital format will help to make these places and things more immediate and accessible to them, and thus allow them to better understand the literary content better.

What drew you to Japanese culture?

CC: I’ve always liked it. I’m fortunate to have had the chance to participate in a teaching program in Japanese public schools called the JET program, where I co-taught English to middle school students. I went there early on and subsequently had other chances to return for study and research. As an undergraduate, I studied modern American poetry and art, and I was always impressed by the connections between American culture – both elite and popular – and Japanese culture. For example, haiku, which emerged in Japan in the seventeenth century, was deeply admired in the U.S. by beat generation writers, jazz musicians, and abstract expressionist painters. Americans and Japanese have been deeply fascinated with each other’s cultures since the nineteenth century. Even American comedians reference Japanese culture, however dubiously – John Belushi’s samurai character on Saturday Night Live and Jon Stewart’s Your Moment of Zen, for instance, are both transformations of the culture of medieval Japan.

What types of students are drawn to Japanese culture?

CC: There’s a real diversity of students who take our classes. Most have never studied Japanese before, though it increasingly common that students have taken some Japanese language courses in high school, whether in the U.S. or overseas. Popular culture is a big draw for a lot of students. Many students are fans of Japanese animation, popular music, and film. While our largest enrollments in language classes are at the first- and second-year levels, many students complete four years of Japanese language study, take part in study abroad programs in Japan, and make Japanese part of planning for their careers.

What are some common misconceptions about Japanese culture among students?

CC: There’s often a conception that there is one single Japanese culture consistent through history, or that Japanese culture can be easily understood as represented by the ideas people have of samurai and geisha. There are many aspects of Japanese culture that the Japanese themselves have promoted internationally that are distortions or exaggerations of historical fact. Television and movies produced both inside and outside Japan are part of this, like Seven Samurai, Rurouni Kenshin, or Memoirs of a Geisha. There’s good and bad to this phenomenon, and it’s very appealing and fun. It’s good if it piques student interest and prompts them to find out more.

What aspects of your teaching have changed with experience?

CC: I’m interested in helping students be better writers. I’m also drawn to help students think about how the topics we cover in class relates to their own lives. I would like them to see the things we discuss as ways to help them think about their own experiences and futures. When I think about my own best teachers – the things that made me want to become a teacher – I remember them as the people who introduced me to texts that changed my whole outlook on life. I can’t say I’ve ever managed to feel like I’ve achieved as a teacher the kind of great moments that I experienced as a student, but I keep trying.